Excerpt from Mark Fisher’s 2014 lecture, “The Slow Cancellation of the Future.”

What is the bad news we already know is that the dimension of the future has disappeared. That in some ways that when marooned were trapped in the 20th century still, what is it to be in the 21st century is to have 20th century culture on higher definition screens or 20th century culture distributed by high speed internet actually. So there’s a strange, I mean, what ought to be a strange sense of repetition of a clotted or blocked time, a time that’s in many respects slowed down or flattened or retired or gone backwards. Where the sense of a forward momentum of culture, which isn’t the same as a progress, I’m not arguing that what has disappeared is a sense of the progressive in culture as if somehow 90s jungle was progressed above Robert Johnson. I’m not arguing that.

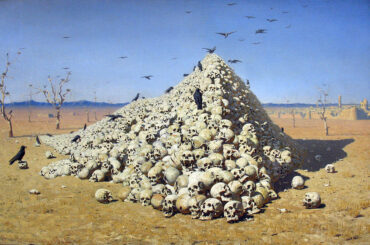

What I’m arguing is that the thing that’s disappeared is a sense of difference or a sense of the specificity, the sense of culture belonging to a specific moment. That is what has disappeared in the 21st century. So now a feeling that nothing ever really dies, but that’s not good. That means that we are assailed on all sides by kind of zombie forms, which persist forever by revivals. Anything can come back.

Anything can come back. There’s a kind of what we might say excessive tolerance for the archaic. But part of the problem is, since the sense of historicity has waned, has declined, it’s difficult to characterize anything as archaic anymore. What does it mean to say something archaic in a situation when practically everything feels old? The phrase that captured this for me and which I use at the start of Ghost of My Life from Franco Berardi is the slow cancellation of the future.

The slow cancellation of the future, I think, which captures not only that sense of termination, but the gradual nature of it. Of course, it’s not that the future in culture disappears overnight. We might look back upon boredom as somewhat utopian proposition now, in many ways. The dialectics of boredom coming out of situationism and going into punk, what are the politics of boredom? The idea of boredom as a kind of existential challenge, that boredom presents us with the blankness of death, the necessity for us to actually do something as a kind of existential injunction.

That’s been eliminated now. That’s boredom, boredom 1.0 no longer exists. I’d say, when I’m in a period, my slogan for this would be, “No one is bored, everything is boring.” What do I mean by that? Well, no one is bored because we’re inundated by microstimuli seamless microstimuli. So the point that we are at a bus stop where you previously would have been bored, now, what is the first thing we do?

We reach for our phones in order to cover over that kind of terror of boredom. That doesn’t really get rid of our experience of boredom, but it doesn’t stop things being boring. I think the particular lure of a lot of 21st century culture is this mixture of curiosity and boredom at the same time. We’re sort of bored even as we’re curious about things, actually. That kind of engine of, as we’re kind of insomniacally drifting through social media at night, we’re kind of, with some level, we’re bored even while we’re kind of curious.

But since there’s no reprieve from the the urgencies of cyberspace, that’s what I mean by no one is bored. We don’t have the freedom to be bored anymore, because on another level, we’re tethered in. We’re fascinated even as we are bored. We’re distracted from our own boredom. We’re distracted from the boring nature of things by the fact that we’re always kind of, we’re subject to these kind of idiotic compulsion.

And again, I think that there’s a lot of Bifo’s work on this, it’s very important. The inundation of the nervous system by stimuli, producing this insomniac state of where it’s no longer possible to dream anymore. And actually, it’s a quite interesting post on the Plan C website from this anonymous group called the Institute of Precarious Consciousness or something like that. Well, they argue we’ve really shifted from an age of boredom to an age of anxiety that with Fordism, the previous regime, dominant regime, and capitalism presented the problem of boredom. And you know, you’re in a factory for years.

That’s boring, you don’t want to do it. Capitalism solved that problem. It solved it in a way that always solves everything by the via kind of the fairy tale genie solution, which is okay, you don’t want to be bored. I’ll make sure you’re not bored, you’ll be anxious forever. And this this kind of, that’s the you know, that’s this sense of kind of universal anxiety.

And I think it’s another thing which prevents us from from experiencing boredom anymore, which doesn’t stop culture being boring. Culture is boring, but there’s no one who isn’t preoccupied all the time who can access this boredom . And so I think what this this calls for, then is, you know, a politics of time and understanding, you know, these different quantitative experiences of time, and how they and how they know this is that the attack on the unpressured unstressed, that time free of urgency is part of the is part of the domination of capitalism over culture at the moment. And what can almost pose this a metaphysical level struggle, there’s one there’s a set of forces that want us to be permanently anxious, permanently have our attention permanently fragmented, permanently dispersed. And that that is definitely winning.

That is that that’s the that’s the dominant force at the moment, against another kind of sense of time, another kind of attractor, which is, you know, where towards this unpressured expansive, more open sense of time, which is now kind of radically fugitive thing, it’s very, very hard to get hold of that.

Source: YouTube